Everybody is familiar with some major funding scandals in the headlines, as exemplified by Watergate, the impeachment of Brazil’s President Collor de Melo following accusations of corruption, or the UK Ecclestone affair. Concern has sparked initiatives like Money, Politics and Transparency project designed to encourage the public to “follow the money”.

Concern is well justified. The Perceptions of Electoral Integrity (PEI) index, a worldwide expert survey, has shown that campaign financing is regarded as the most problematic stage in the electoral cycle. This remains true for both long established democracies like America, as well as full-fledged autocracies like Belarus.

To mitigate problems arising with campaign financing, countries have implemented various policies, including disclosure and transparency requirements, contribution caps, spending limits, and public funding. The general expectation is that these regulations make elections fairer for parties and candidates without well-to-do donors.

But in a comparative perspective, do regulations on campaign finance really bolster the integrity of elections?

New evidence suggests that they do – under certain circumstances. In PEI experts were asked to assess the quality of all stages within the electoral cycle, including campaign finance, such as any problems arising from the misuse of state resources, the equitable access to public money. and the transparency of campaign finance.

International IDEA, another intergovernmental organization providing electoral assistance, collects evidence about the regulation of campaign finance in countries worldwide. This includes: Monetary limits on donations and spending, bans of certain donor groups and reporting obligations of both candidates and parties. Besides the influence of public subsidies, IDEA thus covers all aspects of campaign financing. Theoretically all these regulations can be expected to have a positive influence on the fairness of campaign spending. To develop a measure of campaign finance regulations, the number of existing regulations per country can be summed.1 The assumption behind this measurement is, as more the campaign financing process is regulated and constrained by law, as higher the chance for a fair electoral environment.

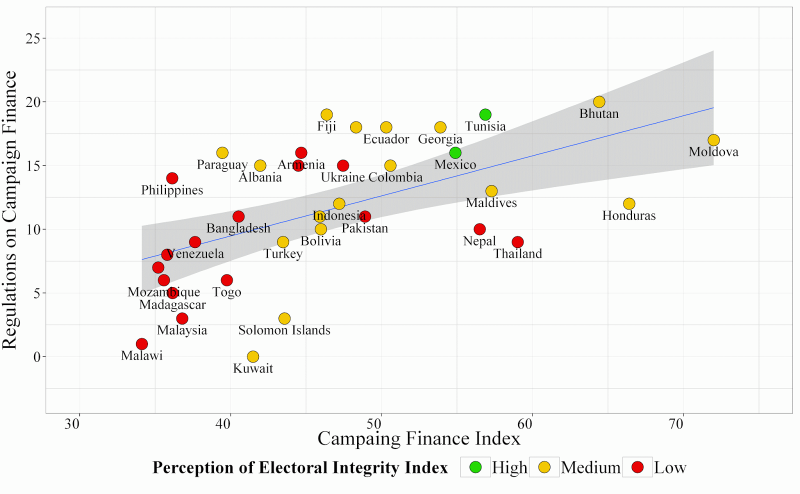

The results are quite surprising and some of them are shown in the graph. More regulations have an influence on the electoral fairness. But while the effect is rather low in autocracies and democracies, regulations can have a strong impact on Hybrid Regimes, coded by Freedom House as “partly-free”, which provide certain liberties and competitive elections, but malfunction in other regards. Kuwait, Turkey, and the Ukraine are in this group.

The graph above shows the link between campaign regulations and financial integrity in these countries. The PEI Campaign Finance Index is drawn on the horizontal x-axis. The vertical y-axis indicates the amount of regulations, while the rising blue line shows us the effect of regulations on financial integrity. The points in the chart show the actual position of a country. For instance, the state of Moldova, deeply involved in border issues in its east and far from being a democracy, is perceived to have very fair campaign financing, while it strongly regulates campaign financing. The opposite is true for Malawi. Here regulations are low, as well as fairness in campaign financing.

Abbildung/Figure: Campaign Finance Index

What are the lessons? Regulations can make a difference – especially in hybrid regimes. In autocracies they are less effective, because the regimes tend to abuse campaign finance regulations as a tool to suppress opposition parties. In democracies, laws seem to be insufficient to strengthen campaign finance integrity. Effective regulations are accompanied by other factors, including an electoral monitoring body which is capable of enforcing the laws, and a political culture where access to public money is distributed on an egalitarian basis and corruption is restricted.

-

Since there is no assumption whether spending limits are more or less important than reporting commitments, the aggregates are not weighted. ↩︎